Does the basement of your New York City building experience flooding without any apparent explanation like a burst pipe or dramatic weather event? One possible cause is that the water is coming from an underground river.

Turns out NYC is teeming with these once-active rivers and streams that were transportation routes to the former towns and villages and provided freshwater (as opposed to the Hudson River's saltwater) for drinking—and used in pre-Prohibition breweries in Yonkers. Most have since been buried under the proverbial concrete jungle starting in the late 1800s.

Some of these storied streams are well-documented—there's Minetta Brook in Manhattan (which can be traced by the curve of Minetta Lane), Sunswick Creek in Queens, Wallabout Brook in Brooklyn, and Tibbets Brook in the Bronx, which is being "daylighted" (aka restored) in a massive undertaking by the city. But many others remain unnamed.

According to Sergey Kadinsky, an expert on underground rivers and the author of "Hidden Waters of New York: A History & Guide" and its companion blog, a lot of city streams have been forced under the street but it's still easy to spot them.

"When you see dips in the landscape, there was likely a stream there because water goes to the lowest point in the terrain." (When I said I walked on a pretty steep incline in my Upper West Side neighborhood, he immediately guessed that it was on 96th Street near Riverside Drive, where sure enough there used to be "an indentation in the Hudson River called Stryckers Bay." Similar inclines are on 106th and 125th streets.)

Named or not, at least some of these waterways have been known to seep into basements. And when they do, it helps to be able to identify the reason.

"Knowing that flooding is coming from an underground river can help guide you in knowing what to look for and what can be done in terms of treatment and maintenance," says Marat Olfir, resident manager of The Future Condominium in Kip's Bay. In 2015 and 2016, he began noticing lots of water coming up through cracks in the basement, but only from mid-March to mid-April. "I was thinking, what is causing this? There is no heavy rain or snow outside, but then I realized the snow was melting in the mountains and causing the water tables to rise." (Olfir's post on LinkedIn prompted this article.)

If this scenario sounds familiar, read on for how to determine if a river is to blame and what you can do to tame the tide and prevent further flooding.

Find out if your building sits on a buried river

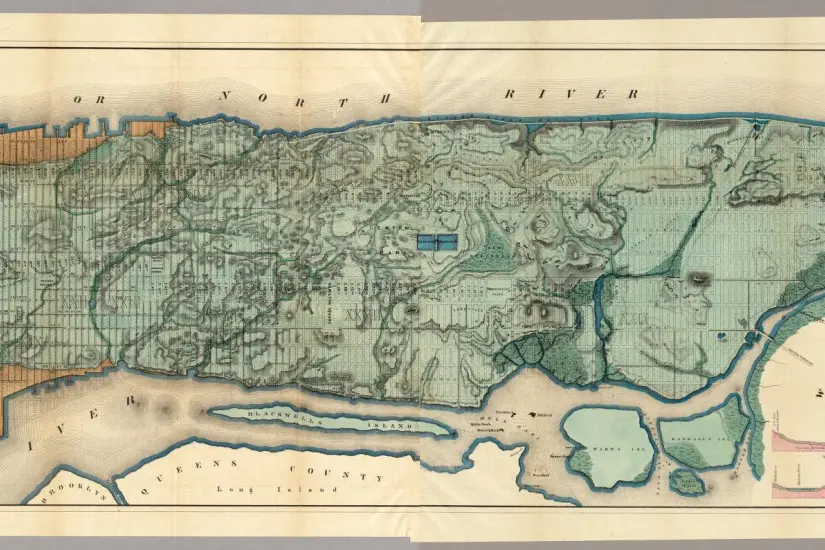

In 1865, an engineer named Egbert L. Viele supervised the creation of a "Sanitary & Topographical Map of the City and Island of New York," shown at top. Anyone can export the map for free or even view it with a georeferencer, which shows the precise coordinates.

"The Viele map is still the best source for historical waterways in NYC and what architects and engineers use as a guide," Kadinsky says. (It appears on the cover of his book, too.) For example, The New York Times recently called Kadinsky to find out if flooding in the basement of The Cathedral at St. John the Divine was due to a buried stream, and the answer was yes.

"The spring is on the Viele map. It's a tributary of Harlem Creek, which includes today's Harlem Meer and The Loch at the northern end of Central Park," Kadinsky says. (According to The Times article, when the original builders discovered underground springs in 1893, they squelched plans to erect a colossal tower and instead went with the more modest version you see today.)

Bill Payne, founder of Payne Engineering PC, a structural engineering firm specializing in restorations and water intrusions, confirms that the Viele map is his go-to source—and has been for decades.

"Many years ago, I remember testing the 30-inch-thick wall in the parking garage at Mount Sinai Hospital, which was a couple stories underground, to see where the leaks were coming from—and water shot out 10 feet from a three-hole like a fire hose. I learned a lot about underground streams in NYC," he says.

Olfir was tipped off on the map by The Future's engineer.

"We thought a pipe had broken or something and would put blowers and dehumidifiers to dry it out, especially in the electrical room where the water would rise to a few inches below the massive wires and was a safety concern," he says. When they had the water analyzed to determine the appropriate waterproofing materials to use, it turned out to be fresh water. "That's when the engineer showed me Viele's map and said, 'Your building is right there, brother.'"

By coincidence, Daniel Wollman, CEO of Gumley Haft, a NYC property management firm specializing in board clientele, managed The Future right after it was built in the 1990s but doesn't recall any such flooding at that time.

That said, two other buildings—one on East 79th Street and another on West 76th Street—sat on top of an underground stream. "We were able to ascertain that the water was coming from a source underneath rather than around or above (like a burst pipe). It wasn't like we had gallons and gallons of water flooding through the basement, but we clearly had a leak," Wollman says.

Other flooding from underground water

Not all water from underground is due to a stream, however. Kadinsky, who has consulted on these types of projects, explains that "it can be hard to determine whether it's a natural source or a century-old water main because those are long overdue for upgrades. Even if a stream is buried under the building, that might not be the source of the leaks or flooding."

Payne backs that up. "Sometimes seasonal infiltrations are caused by rising water tables rather than an underground stream—so even if you are on a stream, you can have water table issues such as after a heavy rain." And he says broken water mains are very common in NYC, too.

Indeed, the water supply turned out to be the cause of recent flooding in a building currently managed by Wollman. "The Department of Environmental Protection is responsible for the water supply that runs down the middle of the street but you are responsible for the branch that runs to your building, and it took them four days to determine that it wasn't coming from our building, but we had to get a second sump pump in there in the meantime because we were taking in enough water."

In yet another instance with similar circumstances, the DEP determined the water was coming from our branch of the infrastructure "and we had to get a second pump in there too—and then shell out $75,000 to fix the problem."

Payne says it's important to pinpoint the precise cause of flooding from underground water because water tables can rise and fall, whereas underground streams have higher pressure and can be harder to deal with and require different solutions.

No comments:

Post a Comment