We Co. had $2.5

billion of cash as of June 30. At its current rate of cash burn—about

$700 million a quarter—it would run out of money some time after the

first quarter of 2020 @eliotwb https://www.wsj.com/articles/wework-faces-cash-needs-as-botched-ipo-scuttles-planned-infusion-11569846537 …

WeWork Needs Cash as Botched IPO Scuttles Planned Infusion

Following

a botched IPO attempt and the ouster of its CEO, WeWork is planning

thousands of job cuts, putting extraneous businesses up for sale and

shedding some luxuries to stop bleeding cash.

wsj.com

As we noted recently,

the most immediate task facing WeWork is that once the IPO was called

off, it unraveled a $6 billion financing package. It is also the

gargantuan challenge facing the company’s two new co-CEOs brought in to

replace Neumann – Sebastian Gunningham and Artie Minson – who have to

find a way forward for a company that was until just a few weeks ago one

of the world’s most valuable private startups with a valuation of $47

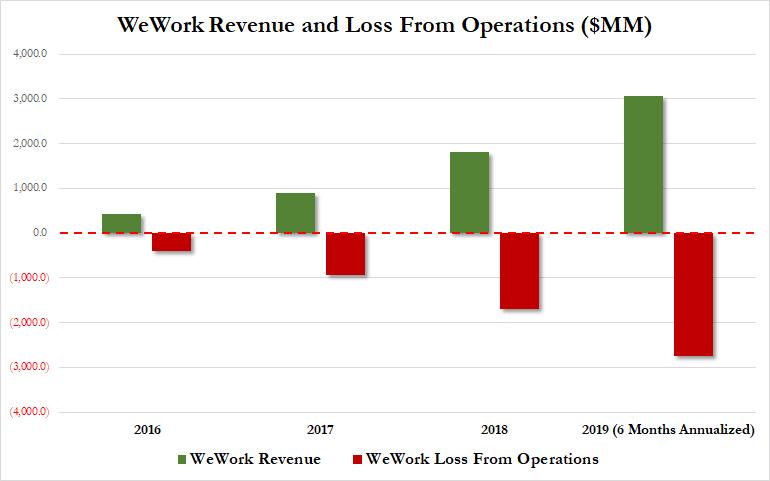

billion… but has not only never made a penny in profit but saw its

losses grow the more its revenue increased.

There is one final option: going to Masayoshi Son’s, SoftBank, the Japanese company that has already pumped in more than $10 billion, hat in hand and begging for a bailout. But is Son willing to jeopardize the future of his VisionFund, and perhaps his entire organization, to throw even more money after what is clearly a terrible investment?

For now, the answer is unknown. What is known is that the company lost $690 million in the first six months and is expected to generate a loss from operations approaching $3 billion as it burns through tens of millions in cash daily. Which means that according to analyst estimates, with its existing $2.5 billion in cash as of June 30, the company could run out of money by mid-2020.

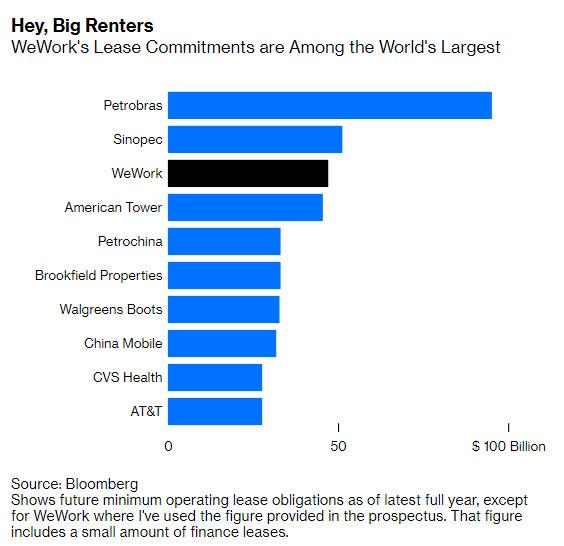

And then there is the real liquidity crisis staring everyone in the face: as part of its tremendous growth, by the end of 2019 WeWork will have not only burned $6 billion since 2016, but will have accrued $47 billion of future rent payments due in the form of lease liabilities. On average it leases its buildings for 15 years. Yet as Bloomberg reported previously, its tenants are committed to paying only $4 billion, and on average have leases for 15 months.

In short, a WeWork solvency crisis (read: bankruptcy) would send a shockwave across the US Commercial Real Estate market. Correction, it would send a shockwave across the global commercial real estate market. The reason is that with over $47 billion in lease liabilities, WeWork is already one of the world’s largest lessees, trailing only oil exploration giants Petrobras and Sinpec, an astonishing feat for the flexible office space provider “which was founded less than a decade ago, bleeds cash, and doesn’t plan to become profitable any time soon.”

And then there is the not so subtle fact that WeWork is already the single biggest tenant in New York City, as well as Chicago, Denver and central London.

Said otherwise, a WeWork insolvency would send the Commercial Real Estate market in New York, London, and most major metropolises into a tailspin.

Which brings up the next logical question: who is exposed?

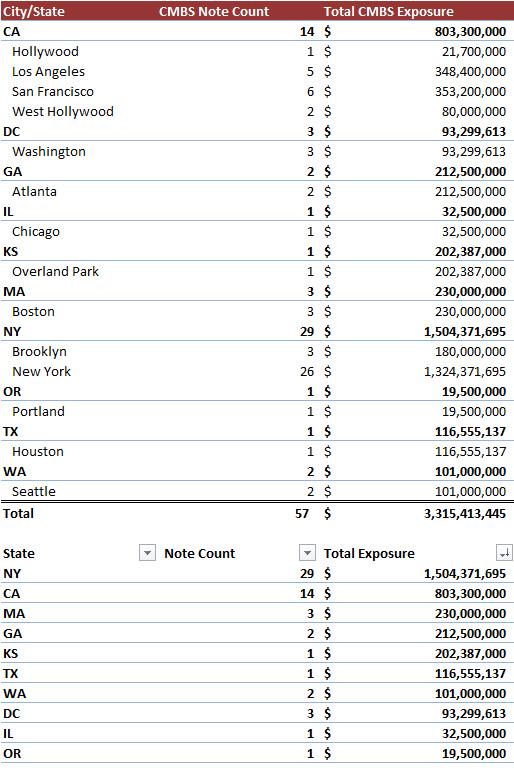

Luckily, commercial real estate expert TREPP has already done work when it comes to WeWork’s US-facing exposure in the CRE realm and has found that co-working giant is flagged as a top five tenant behind $3.3 billion in CMBS debt across 36 properties. Courtesy of Trepp, here is a summary of WeWork’s exposure by state, which as expected, shows New York and California as the top CMBS markets with WeWork exposure.

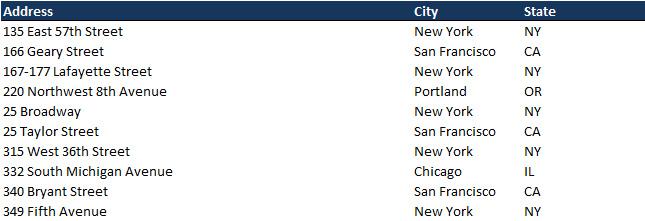

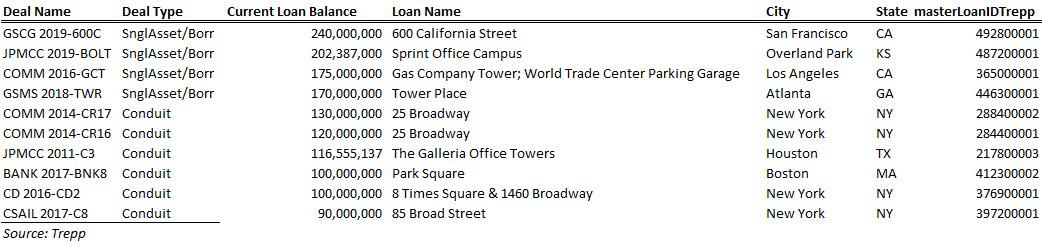

Drilling down on some of the key properties, we find the following Top 10 locations that will find themselves scrambling to undo their billions in contractual exposures to a potentially insolvent WeWork:

Here is a different way of representing the exposure, this time from the Deal side perspective:

Readers seeking the full list of WeWork exposure are urged to contact Trepp directly.

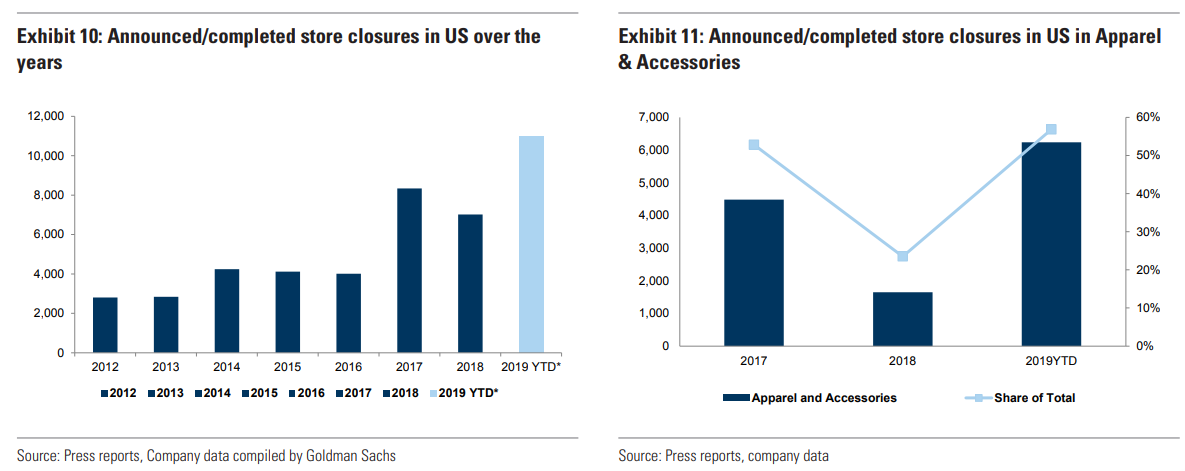

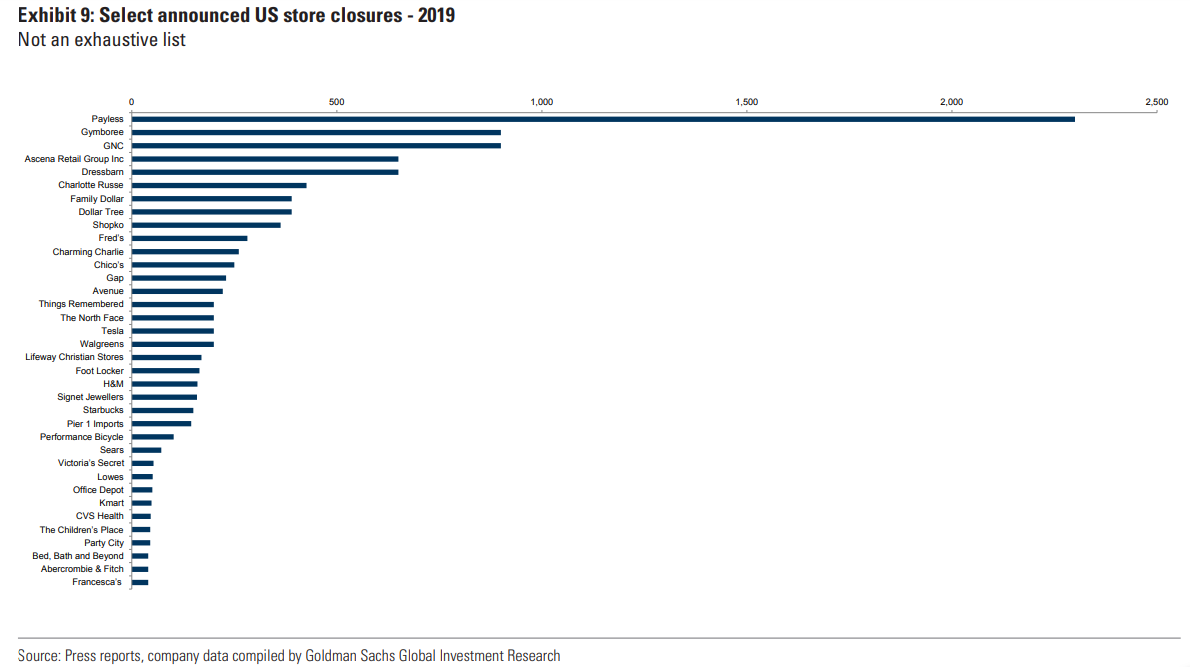

For those asking why is any of the above information relevant, the answer is simple: in a year when a record 11,000 stores are expected to shutter…

… as a result of the ongoing “retail apocalypse” which today claimed its latest victim, fast-fashion pioneer Forever 21, which is set to close as many of 350 of its 800 stores around the world…

… commercial real estate is looking at an unprecedented rental payment “hole” as countless tenants file for bankruptcy and put their lease payments on indefinite halt.

Throw WeWork – and its $47 billion in lease obligations in the mix – and CRE is facing a CREsh of epic proportions, because in a bankruptcy, all those obligations would be frozen and squeezed among all the other pre-petition claims, which of course means that the commercial real estate market of cities where WeWork is especially active – like New York and London – would suddenly find itself paralyzed, as a deflationary tsunami is unleashed among one of the strongest performing markets since the financial crisis.

Whether that will in fact happen remains to be seen: after all, with so much hanging on whether the cashflow burning WeWork lunacy can continue, one could argue that when it comes to the commercial real estate market, the company has become too big to fail.

That’s precisely what Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren said on September 20, when he warned just how serious WeWork’s leveraged debacle has become. In a speech delivered to New York University, the Boston Fed head seems to have seen the light, fearing financial instability from WeWork and its ilk:

Mr. Rosengren noted the risks posed by commercial real estate, which have long been a concern of his, as a possible vector to amplify trouble.

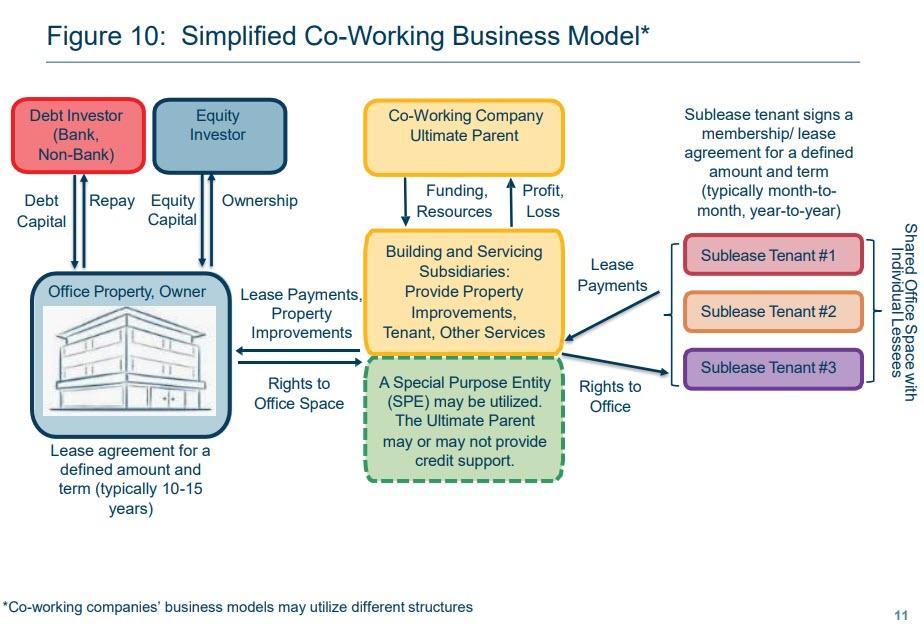

Without naming any firms, Mr. Rosengren noted the particular concerns posed by co-working companies. He made this comment as the parent of office-sharing firm WeWork postponed its initial public offering amid investor doubts about its valuation and concerns about its corporate governance. Office-sharing firms are particularly exposed to risks should the economy run into trouble, and could wound landlords in the process, Mr. Rosengren said.

“In a downturn the co-working company would be exposed to the loss of tenant income, which puts both them and the property owner at risk if they cannot make lease payments to the owner of the building,” he said.

“I am concerned that commercial real estate losses will be larger in the next downturn because of this growing feature of the real estate market, which could ultimately make runs and vacancies more likely due to this new leasing model,” Mr. Rosengren said.

“The fact that the shared office model relies on small-company tenants with short-term leases, combined with the potential lack of recourse for the property owner, is potentially problematic in a recession. This also raises the issue of whether bank loans to property owners in cities with major penetration by co-working models could experience a higher incidence of default and greater loss-given-defaults than we have seen historically.”

Ironically, unless some last ditch source of emergency WeWork funding emerges – and there is about 6 months for that to happen – Rosengren’s warning about a crash in the commercial real estate market will come true. Why ironic? Because it will be none other than the Fed which will be “forced” to provide said emergency funding, making the global moral hazard hole even deeper in a world in which not even one too big to fail zombie company is allowed to fail ever again.

https://www.zerohedge.com/economics/here-are-billions-loans-exposed-potential-wework-bankruptcy