-WHITE HOUSE OFFICIAL

The U.S. Justice Department on Monday urged attorneys across the legal profession to volunteer their time to assist the crush of tenants expected to be forced out of homes now that a COVID-19 pandemic-related eviction moratorium has ended.

The move came four days after the U.S. Supreme Court https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-supreme-court-ends-federal-residential-eviction-moratorium-2021-08-27 ended a federal moratorium aimed at keeping people housed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Democratic President Joe Biden and top members of his party in Congress blasted that decision but have not taken further emergency action to stop what could be a wave of evictions.

In a letter https://www.justice.gov/ag/page/file/1428626/download addressed to "members of the legal community," Attorney General Merrick Garland said eviction filings are expected to spike to roughly double their pre-pandemic levels and that lawyers have an ethical obligation to help the most vulnerable.

"We can do that by doing everything we can to ensure that people have a meaningful opportunity to stay in their homes and that eviction procedures are carried out in a fair and just manner," Garland said.

Garland's letter encouraged lawyers to volunteer at legal aid providers, or to help tenants apply for emergency rent relief through government programs.

Garland said "the vast majority of tenants need access to legal counsel because far too many evictions result from default judgments in which the tenant never appeared in court."

The nation's top court on Thursday granted a request by a coalition of landlords and real estate trade groups to lift the moratorium by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that was to have run until Oct. 3, saying it was up to Congress to act.

Over 60 Democrats in the House of Representatives pushed for congressional leaders to take action, writing a letter urging House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, both Democrats, to revive the national eviction moratorium for the rest of the pandemic.

Congress approved $46 billion in rental assistance earlier in the pandemic, but the money has been slow to get to those who need it, with just $3 billion issued through June for rent, utilities and related expenses, according to U.S. Treasury data.

Within hours of becoming New York’s 57th governor, Kathy Hochul vowed to speed up the release of more than $2 billion in federal rent relief.

Hochul on Tuesday said she plans to hire additional staffers to process applications for the state’s emergency rental assistance program, or ERAP, and is “assigning a top team to identify and remove any barriers that remain.”

“I am not at all satisfied with the pace that this Covid relief is getting out the door,” she said. “I want the money out — and I want it out now. No more excuses and delays.”

According to a press release distributed after her speech, the state will reassign 100 contracted staff members to work one-on-one with landlords on rent relief applications. The state will also dedicate another $1 million to marketing and outreach related to the program.

Hochul was sworn in after midnight on Tuesday, following the resignation of Andrew Cuomo.

Ahead of Hochul’s address, Joseph Strasburg, president of the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlord group, said the new governor’s “most daunting and pressing task on day one” is to ensure the relief is distributed to landlords and tenants at “lightning speed.”

“The new governor must understand that landlords and their tenants have been desperate for this financial lifeline since last year,” he said in a statement. “She must not allow New York lawmakers to continue to play politics with this process with the looming expiration of the statewide eviction moratorium.” The ban expires Aug. 31.

The rollout of ERAP has been plagued by technical difficulties and delays. As of earlier this month, only $100 million of the $2.7 billion in federal aid had been dispersed. According to Hochul’s office, the state has “either distributed or obligated more than $680 million in federal funding, including more than $200 million in direct payments to landlords” since it started accepting applications in June.

The agency charged with running the relief program, the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance, testified during an Aug. 10 hearing that much of the remaining funds would not be distributed before the state’s eviction protections expire at the end of this month.

During her speech, Hochul emphasized that landlords who receive funds through ERAP cannot evict their tenants for one year, though there are some exceptions. It is not clear if she will heed the call of tenant advocates and support extending the state’s protections beyond the end of this month.

On Aug. 12, Hochul said she would work with lawmakers to strengthen eviction protections after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a provision that permits tenants to self-report Covid-related financial hardship with a form as a defense against eviction. Although the state’s protections expire at the end of this month, a federal ban in high-Covid counties lasts through the beginning of October. Last week, real estate groups petitioned the Supreme Court to halt the latest federal moratorium.

https://therealdeal.com/2021/08/24/kathy-hochul-pledges-to-speed-up-rent-relief-rollout/

The federal government has paved the way for civil servants to work in coworking and flexible office spaces, awarding contracts to five flexible workspace companies.

The General Services Administration, which manages real estate and procurement for all federal agencies, has awarded Flexible Coworking Services contracts to WeWork, LiquidSpace, Deskpass, Expansive and The Yard.

"The contracts are part of a much longer process set in motion back during the Obama administration," LiquidSpace CEO Mark Gilbreath told Bisnow Thursday morning. "The federal government is rethinking how it uses office space, with the goals of economic efficiency, sustainability and a better worker experience."

The government anticipated a shift in office working patterns before the coronavirus pandemic — it posted the solicitation for flexible office providers in early 2020 before announcing the award last week. When the pandemic came, that kicked the movement away from traditional office use into higher focus, Gilbreath said.

"A myriad of companies across many industries have initiated or accelerated their move toward nontraditional office space," Gilbreath said. "The GSA should be applauded for setting this vision in motion pre-Covid. The agency was right before the pandemic made it obvious to everyone else."

The GSA is paying $50M across the five providers, 50% of which will go to four of the participants under the small business designation, Expansive CEO Bill Bennett wrote on LinkedIn.

"The pandemic has fundamentally changed how work is approached, and now government agencies will have a tool to help employees succeed while saving costs,” WeWork CEO Sandeep Mathrani said in a statement. “The workplace of the future requires flexibility."

In June, President Joe Biden's administration directed federal agencies to draft long-term policies for their workplace and remote work strategies, stressing maximum flexibility. Experts in government office leasing expect the government's long-term leased space to shrink by millions of square feet in the coming years, Bisnow reported last week.

"There are going to be a lot of instances where the government will either vacate buildings outright and consolidate into other locations or simply downsize as a function of the pandemic," Colliers Executive Vice President Kurt Stout, who leads the brokerage firm's Government Solutions group, told Bisnow.

The five companies encompass a variety of spaces and leasing models. For example, WeWork subleases space to customers in various locations, mostly urban, Expansive owns its space (currently 39 locations), and LiquidSpace is a platform on which owners list their space and would-be tenants find it, thus potentially facilitating the leasing of any amount of space for any amount of time.

Deskpass, which specializes in on-demand workspaces, stressed the efficiency of its pricing model for the GSA. The agency will only pay for the desks, meeting rooms, and private offices it needs and only on the days it needs them, according to the company.

The GSA manages more than 7,800 federal office leases totaling more than 181M SF in markets across the country, overseeing space for about 2 million workers, so giving even a small fraction of its space to coworking "represents a huge opportunity," Francesco De Camilli, Colliers International vice president and head of flexible workspace consulting, told Bisnow in 2020 after the government posted its solicitation.

"Their approach is to pick the best-in-market operators, not to establish a single point of contact with a national platform," De Camilli said.

Emergency response teams that need to set up offices following a hurricane would be a candidate for flexible, short-term space, De Camili said, and other project-based initiatives would find such space equally useful. Some federal budgets are set for 12-month periods, so flexible space means that real estate contracts can follow the same short terms.

"Working beyond the confines of traditional government offices has become more common," the GSA said in its request for proposals for flexible workspace in early 2020. "Government employees are now commonly equipped with technological tools to work from anywhere. The freedom provided by technological advancements allows agencies to efficiently and flexibly pursue mission success through the utilization of employee mobility and telework."

The past year has been a fiscal nightmare for Nashville. Covid-19 helped punch a $332 million hole in the city’s $2.46 billion budget. Tennessee state comptroller Justin Wilson warned that, without drastic action, the state might take over management of Nashville’s affairs. In response, the city council raised property taxes 34 percent, spurring a citizen revolt in the form of a ballot initiative to overturn the tax hike. Without the extra revenue, however, Mayor John Cooper’s administration said that drastic cuts would be unavoidable: “Few corners of the Metro government, including emergency services and schools, would be spared significant reductions or eliminations.”

Nashville’s budget woes predate the pandemic: the city began borrowing money to cover deficits after the Great Recession of 2008–09. City leaders, at the same time, went into heavy debt to build new government-owned attractions, offered workers health retirement benefits that they haven’t funded, and deep-sixed pension reforms that saved the state billions of dollars. In fact, back in December 2019, the state comptroller issued a similar warning to Nashville about its shaky finances.

The Music City isn’t alone. The Covid health emergency and accompanying economic downturn caused budget crises for municipalities—cities, counties, and school districts—across America. A February letter from 400 mayors to President Biden said that the pandemic-inflicted strain on municipal budgets had “resulted in budget cuts, service reductions, and job losses” throughout local government. America’s largest city, New York, grappled with a nearly $10 billion budget deficit in the spring of 2020, while Chicago struggled with a $2 billion gap. Dozens of local governments used the crisis to justify budget maneuvers that fiscal experts generally frown upon, from borrowing money to close deficits to issuing bonds to fund employee pensions.

But as with Nashville, the fiscal difficulties afflicting many local governments over the last year result from bad financial practices that preceded the pandemic and left cities and school districts ill-prepared to cope with shutdowns. Some governments—again, like Nashville—began borrowing money to close budget deficits after the last recession a decade or more ago and never dug out from those debts. Others, including a number of California municipalities, built up such large funding gaps in their pension systems that, even during the long national economic expansion prior to 2020, they were using pension-obligation bonds (POBs) to conceal their problems. One study assessing the fiscal health of America’s biggest local governments for the immediate pre-pandemic period found that 62 cities lacked the resources to pay all their bills. “This means that to balance the budget, elected officials did not include the true costs of the government in their budget calculations and pushed costs onto future taxpayers,” the study concluded.

Even the tens of billions of dollars the Biden administration is showering on local governments won’t fix their long-term financial troubles. Only genuine reforms that banish unsound budget practices and use economic expansion to prepare for fiscal downturns will reverse a trend that has seen local governments go into hock and stay there for extended periods—at great cost to their residents.

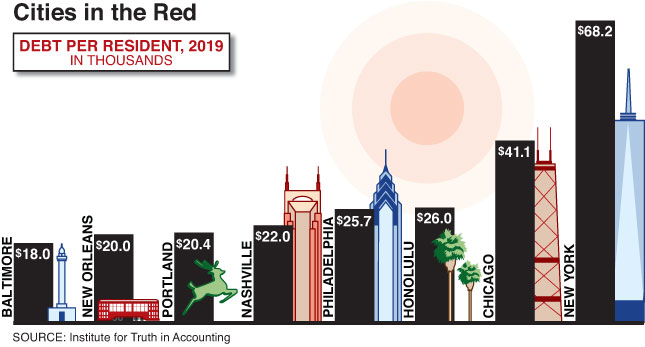

The financial state of America’s largest cities heading into the Covid-19 crisis was worse than the reports on the budgetary fallout from lockdowns generally acknowledge. An Institute for Truth in Accounting study of the nation’s 75 largest cities, based on their 2019 comprehensive annual reports, found that, collectively, they owed a jaw-dropping $333.5 billion more than they had saved. Much of that debt, moreover, is for benefits that employees had already earned but that cities have yet to fund. “One of the ways cities make their budgets look balanced is by shortchanging public pension and OPEB [retiree health benefit] funds,” the institute noted.

Distressingly, the study found that only 13 cities legitimately balanced their budgets—that is, paid all their bills without using fiscal gimmicks such as pushing off into the future payments that they should be making now. The study identified a few winners, including Irvine, California; Lincoln, Nebraska; and Charlotte, North Carolina. But for other cities, the picture is darker. Among those with future obligations far outstripping current resources are New York, which collectively owes $194 billion that the city hasn’t funded, or $68,000 per every city taxpayer; Chicago, with an unfunded debt load of $36 billion, or $37,000 per taxpayer; and Nashville, with $4.3 billion in debt that it doesn’t have resources to pay, amounting to $22,000 per taxpayer.

New York headed into 2020 after a decade of prosperity that saw the city’s economy add hundreds of thousands of new jobs and government boost spending by nearly 50 percent, or $29 billion. Led by Mayor Bill de Blasio for much of that period, New York largely spent that affluence to fatten government, doing little to bank money for a rainy day or reduce its growing unfinanced debts. When Covid struck, de Blasio declared that the city faced a “wartime budget” that would force it to slash some $3.5 billion immediately and perhaps an equal amount in the coming fiscal year. Among other things, the administration moved to reduce basic services like trash collections and cut the number of traffic cops on duty.

Much of New York’s budget mess owed to its extraordinary workforce costs, which far exceed those of other cities. Rather than try to restrain those costs, de Blasio—elected with heavy support from public-sector unions—expanded the size and price of the city’s workforce over eight years. During his tenure, increases in compensation accounted for half the budget’s expansion, with the city workforce growing at the fastest rate in decades—adding 30,000 workers at an average cost of $151,000 per worker.

One example of the excesses: Gotham has made lavish promises to workers to finance their health care in retirement, with virtually no contribution from workers themselves—something rare in the private sector and most of government. Every year, the future cost of funding these promises swells by more than $5 billion. Instead of putting this money aside (or reducing the benefit to more affordable levels), the city spends its tax revenues elsewhere—so that, during de Blasio’s tenure, this debt rose from $75 billion to roughly $115 billion. Meantime, the annual cost of paying the benefit itself, which must come out of the city’s everyday budget, has reached about $3 billion and will double in the next decade. By then, without some effort to pay off the debt or reduce the benefits, the city will owe $200 billion for retiree health care that it hasn’t financed. What money the city had put aside for long-term health costs (just 4 percent of what it owed), de Blasio promptly swiped to help close its pandemic budget gap.

Other thriving cities also spent the pre-virus years mortgaging their futures. Nashville has been a boomtown over the last decade, its population up 12 percent, the local economy growing by some 300,000 new jobs, and its tax revenues expanding 50 percent. Yet in the familiar pattern, at the first sign of economic slowdown a decade ago, city leaders chose not to restrain budget growth but instead engineered a notorious “scoop-and-toss” financing scheme—issuing bonds to make payments on current debt (thus, scooping up current obligations and tossing them into the future). At the same time, aspiring to be a world-class city, Nashville borrowed hundreds of millions of dollars to build tourist attractions, from the Music City Center to a minor-league baseball stadium to an amphitheater. The city’s debt payments have thus rocketed from about $80 million in 2011 to $330 million last year. Nashville is also on the hook for $110 million in annual payments to fund its expensive pension system—this, after city leaders refused several years ago to sign on to a pension-reform agenda that Tennessee enacted, which has dramatically slowed the growth of state retirement debt.

Before Covid, Chicago had enjoyed a decade of economic growth, which saw its job numbers climb by 100,000 and its unemployment rate sink to an impressive 3.1 percent by late 2019. But it had also become America’s second-most indebted major city by spending well beyond its prosperity, failing to fund its pension system adequately, using nonrecurring revenues from the sale of city assets to fund popular programs, and regularly issuing new debt to kick current obligations into the future. The annual cost of Chicago’s severely underfunded pension system was so high that the payments consumed all the city’s property taxes; next year, that bill will rise by another $432 million, to $2.2 billion. Chicago spent years after the recessions of 2001 and 2008 borrowing money to finance everyday operating expenses—about $4.5 billion in debt to pay for spending beyond what city revenues could bear. Chicago’s debt payments have exploded to $800 million annually.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot admitted that more than half the city’s projected 2021 deficit was due to its poor finances. And the debt blowout continues. Recently, at the behest of union officials, the state passed an enhancement of Chicago firefighters’ pensions that will add $800 million in new debt to their pension fund, which was only 20 percent funded pre-pandemic. The health emergency has sent Chicago back to the practice of deficit financing. Once the lockdowns began, Chicago had to borrow some $500 million in low-interest short-term loans just to pay its bills, and Lightfoot’s original budget for next year called for a $1.7 billion deficit financing to balance its budget. The federal stimulus, providing the city with $2 billion, will help smooth over budget problems in the short term, though Lightfoot hasn’t discounted future borrowings.

Bad fiscal practices like these are increasingly common among local governments, which claim that Covid-19 required extraordinary measures. A recent study by Matt Fabian and Lisa Washburn of Municipal Market Analytics, examining 442 municipal bond offerings in the second half of 2020, found that at least a quarter used the money for “direct deficit financing” (floating new debt to close budget gaps) or “indirect deficit refinancing” (issuing debt to pay for projects that governments previously had financed with tax revenues). That so many local governments resorted to such financing so quickly—just months after the lockdowns began—suggests how little financial flexibility and reserves many of them had.

Pennsylvania school districts, for instance, have faced huge increases in pension costs because of years when the state legislature awarded benefits to school employees without doing enough to demand that they be funded. With the state teachers’ pension system just 55 percent funded, the state and local districts this year must split a tab amounting to 35 percent of salaries—up from just 8 percent a decade ago. To deal with that burden, some districts resorted to deficit financing after the coronavirus hit. Riverside, a small district near Scranton, has seen its pension payments rise by 75 percent in just five years, to $3.6 million, or 14 percent of its budget, according to its bond documents. Late last year, it floated $1.9 million in bonds that Moody’s described as a scoop-and-toss offering. Rochester, another small Pennsylvania district, confronted some $5 million in debt payments in 2021 and issued approximately $5.4 million in new bonds with later maturities to give itself more time to cut costs and figure out how to repay creditors. Its overall debt swelled.

Questionable financial transactions can spread in states and metro regions like a contagion. Hartford, Connecticut, began using deficit financing to disguise its budget problems after the last recession. Issuing about $200 million in new debt about eight years ago, Hartford eventually found itself struggling with exploding debt payments, which went from $10 million annually to $54 million. The city reached the brink of bankruptcy before the state took control of its finances and engineered a $534 million bailout. Even so, in 2018, nearby New Haven resorted to the same maneuver, floating $160 million in scoop-and-toss debt, though city leaders pledged fiscal prudence to avoid Hartford’s fate. In 2020, New Haven grappled with a new $66 million deficit, which officials described as a “crisis” budget. Though the pandemic worsened the shortfall, much of the problem was structural—that is, the long-term result of the city spending more than it took in. New Haven’s debt service alone comes to $62 million annually; its pension costs have risen $23 million, or 37 percent, in just five years. Nearby Hamden, a community of 60,000, resorted to its own deficit financing last summer, seeking to avoid a cash crisis. It’s now counting on $20 million or so from the Biden stimulus to help ease its budget shortfall.

Low interest rates, propelled in part by the economic downturn, have helped spur a resurgence of another discredited funding tool: the pension-obligation bond. Governments use these bonds to raise money to make their pension systems look better financed, but in doing so, they add new debt to their balance sheets. The rationale for these POBs is that municipalities can borrow money and pay back creditors at 3 percent to 4 percent, and then invest the proceeds in their pension funds to earn 7 percent or more—the typical target for stock-market returns of most public pension systems.

What this thinking overlooks is that markets don’t just rise; they also fall, and pension funds in the past have lost money that they borrowed. That risk is what led the Government Finance Officers Association to issue a warning: “POBs involve considerable investment risk, making this goal [of achieving adequate investment returns] very speculative,” the organization says. “In recent years, local jurisdictions across the country have faced increased financial stress as a result of their reliance on POBs, demonstrating the significant risks associated with these instruments for both small and large governments.” Those risks are especially steep now, with the stock market at an all-time high, rebounding by 79 percent since its March 2020 selling frenzy.

Pension-obligation bonds played a role in some notable municipal bankruptcy cases after the last recession. Stockton floated some $125 million in bonds in 2007 and gave the proceeds to the California state pension system to invest. The city promptly lost one-quarter of that money in the market decline of 2008. Coupled with Stockton’s already-inflated pension obligations, the losses helped drive the city into bankruptcy. Detroit, for its part, engineered a $1.4 billion offering in 2006, using a complex funding structure that sought to borrow in a way that evaded state debt limits. The added debt led a financial trustee, brought in to manage the city’s affairs, to seek bankruptcy on its behalf. Bondholders wound up getting just 14 cents on the dollar for what remained of the debt; city workers took an approximate 9 percent cut in their pensions.

Despite warnings, the use of pension-obligation bonds has exploded. States and municipalities issued $6 billion in POBs last year, double the previous year’s volume. And more borrowing is coming. “We see no signs of slowing down in 2021,” Todd Kanaster, director for municipal pensions at S&P Global Ratings, predicted. Just a few months into 2021, several cities had already completed enormous POB offerings. Huntington Beach, a midsize California community of 200,000 people, issued $436 million in POBs in March, a sum more than twice its $217 million general fund budget. The city, like many California communities, justified the move because the bill for financing its pensions had risen from $4.6 million in 2008 to $30 million last year. The city is looking at a potential annual bill of $40 million by 2024. But Huntington Beach compounded its fiscal distress when it gave workers raises last April, adding $5 million to its budget over the next three years. Several months later, the city admitted that it expected a $20 million decline in revenues due to the pandemic, and officials began exploring the possibility of raising money in the bond market.

California cities can issue these bonds thanks to a 2007 state supreme court ruling that exempted pension borrowings from a law requiring municipalities to get voter approval for new long-term debt. The ruling, combined with rapidly growing pension costs for local municipalities—collectively, they’ll have to ante up $5.3 billion in 2022, just to cover unfunded retirement debt—has municipalities heading to the bond market, despite the risks. Chula Vista, San Diego County’s second-largest city, with a population of 275,000 and a general fund budget of $197 million, borrowed $350 million earlier this year to offset the rise of its pension costs, which have hit $30 million annually. Much of the city’s fiscal problems go back to generous enhancements to pensions that officials agreed to years ago, allowing workers after 30 years of service to retire at age 60 with pensions at 90 percent of their salaries. So onerous are those promises that the city’s pension debt kept rising, even during the pre-Covid stock-market boom. From 2015 through 2019, the city’s unfunded pension debt increased to $355 million from $234 million, as the S&P 500 was rising by nearly 50 percent.

Huge offerings like these are spreading—and getting ever more creative. Municipalities in Arizona are plagued by huge debts in the state’s public-safety pension systems, which are less than 50 percent funded. To help reduce annual required payments, Tucson raised $659 million earlier this year from a controversial form of borrowing that utilizes so-called certificates of participation. In essence, Tucson sold assets that it owns, including golf courses and a zoo, to a shell corporation, which rented them back to the city. The corporation then sold the certificates, a form of bond, to investors, who will get paid with the “rent” that the city is paying itself. Tucson is depositing the $659 million in its pension fund, hoping for fat investment returns. Some 140 miles north, Flagstaff rented its libraries and other facilities, including City Hall, to itself in order to raise $112 million. If the pension system hits its investment targets, the move will save the city $76 million over 20 years. That’s a big if, though. Certificates of participation carry significant risks. They were behind Detroit’s disastrous pension borrowing back in 2006.

According to many local leaders, the lockdowns brought a budget crisis that could be solved only through extraordinary federal government aid. The Biden stimulus package certainly delivered, dedicating an unprecedented $130 billion to municipalities, on top of hundreds of billions sent to state governments. Yet any survey of what governments owed, and how persistently they failed to balance budgets even during good times, makes it clear that the stimulus money won’t fix the fiscal mess. Pre-Covid, the largest American cities already owed about two and a half times what the administration is showering on localities. All that debt weighs on budgets even when the economy is racing; it becomes a crushing burden after the economy slows down.

The public-health crisis has blunted local reform efforts. Early last year, then–California state senator John Moorlach proposed legislation that required municipalities to get voter approval before they could issue pension-obligation bonds. But as the virus surged, California’s legislature shelved the bill. Free to pile up new debt, state municipalities issued $3.7 billion in POBs in 2020, and they’re adding more in 2021.

Post-Covid, will states try to restrain local governments’ addiction to deficit financing? Officials could pass laws, like Moorlach’s proposed measure, that mandate voter approval of questionable fiscal maneuvers. Or they could ban such tools outright. More broadly, states could impose sensible changes in government accounting principles that make elected officials acknowledge—and pay for—the true cost of their profligacy. Though most states require local governments to balance their budgets, current accounting principles ignore some of the basic costs that those governments incur, such as retirement benefits. Thus, New York City can promise workers every year $5 billion in future retirement health benefits, without needing to finance those benefits today. Compelling elected officials to account for the present value of such benefits (which, in New York’s case, would be less than $5 billion but still substantial) and set aside money out of their current budget to pay for them would reveal the benefits’ true costs. Local officials would have to finance them now—rather than leave the bill to someone else—or reform local spending and avoid unsustainable commitments.

Retirement reforms in many places have been anemic, at best. The state and local pension crisis is now 15 to 20 years old. Many governments lost the opportunity to address it when the debt was manageable. After the 2008 financial crisis, dozens of states claimed that they’d made changes to fix their imbalances. Few succeeded. Most reforms were superficial. If governments had enacted true reforms back then—switching workers to defined-contribution plans that don’t leave taxpayers on the hook for investment shortfalls, or creating hybrid plans that offer workers a small annuity combined with an investment savings account—the situation would look much better.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that local governments are not about to grow their way out of their long-term budget problems, even when the economy booms. Only reforms that force them to confront the true cost of their bills will stem the rise in bad budgeting that leaves them unprepared for any but the best of times.

Steven Malanga is the senior editor of City Journal and the George M. Yeager Fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

https://www.city-journal.org/covid-19-lockdowns-exposed-cities-deep-seated-financial-troubles

Will the end of the foreclosure moratorium, combined with the expiration of a large number of forbearance plans, lead to a surge in foreclosures and impact house prices, as happened following the housing bubble?

Some simple definitions (for housing):

Forbearance is the act of refraining from enforcing mortgage debt.

Delinquency is the failure to make mortgage payments on a timely basis.

Foreclosure is when the mortgage lender takes possession of the property after the mortgagor failed to make their payments. “In foreclosure” is the process of foreclosure.

At the onset of the pandemic, there was a large increase in the number of mortgagors entering forbearance plans with their lenders. This caused some concern that these forbearance plans would eventually lead to a significant increase in foreclosures.

Most of these forbearance plans were for 12 months, with up to 6 months of extensions - for a total of 18 months. Since many of these borrowers entered these plans in April and May of 2020, the 18 months will end in September and October 2021.

Both the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) and Black Knight are providing weekly estimates of loans in forbearance. An analyst at Black Knight wrote this morning:

According to Black Knight’s McDash Flash forbearance tracker, there are now 1.76 million borrowers who remain in COVID-19 related forbearance plans as of August 24 … That number ramps up to nearly 670,000 for September, though, with 415,000 of those plans set to reach their final expiration next month based on current allowable forbearance term lengths.

Here is a graph from Black Knight. The number of borrowers in forbearance peaked at about 4.75 million in May 2020, and is now down to 1.76 million. So 3 million borrowers have already exited forbearance plans.

And from the MBA this week:

According to MBA's estimate, 1.6 million homeowners are in forbearance plans.

This following graph is from the MBA and shows the % of the portfolio in forbearance.

IMPORTANT: The concern isn’t just the 1.6 to 1.7 million borrowers still in forbearance plans, but also borrowers that have exited plans, and are not current. Here is some data from the MBA on the status of borrowers that exited forbearance plans:

Of the cumulative forbearance exits for the period from June 1, 2020, through August 15, 2021, at the time of forbearance exit:

28.3% resulted in a loan deferral/partial claim.

22.6% represented borrowers who continued to make their monthly payments during their forbearance period.

16.1% represented borrowers who did not make all of their monthly payments and exited forbearance without a loss mitigation plan in place yet.

13.1% resulted in reinstatements, in which past-due amounts are paid back when exiting forbearance.

11.1% resulted in a loan modification or trial loan modification.

7.4% resulted in loans paid off through either a refinance or by selling the home.

The remaining 1.4% resulted in repayment plans, short sales, deed-in-lieus or other reasons.

So some of the 3 million or so borrowers that have already exited forbearance plans are also not current.

It is important to note that loans in forbearance are counted as delinquent in the various surveys, but not reported to the credit agencies.

Here is a graph from the MBA’s National Delinquency Survey through Q2 2021.

Note that loans in the foreclosure process were at a record low in Q2 (there was a foreclosure moratorium that ended on July 31, 2021). And short term delinquencies (30 and 60 days) were also at a record low. Loans in forbearance are mostly in the 90 day bucket at this point, and that is the area of concern.

Both Fannie and Freddie release serious delinquency (90+ days) data monthly. Fannie Mae reported that the Single-Family Serious Delinquency decreased to 2.08% in June, from 2.24% in May. And Freddie Mac reported that the Single-Family serious delinquency rate in June was 1.86%, down from 2.01% in May.

This graph shows the recent decline in serious delinquencies:

The pandemic related increase in serious delinquencies was very different from the increase in delinquencies following the housing bubble. Lending standards have been fairly solid over the last decade, and most of these homeowners have equity in their homes - and they will be able to restructure their loans once (if) they are employed.

There are a record low number of properties currently in foreclosure due to the foreclosure moratorium that ended on July 31, 2021. Here is some data from Fannie and Freddie on Real Estate Owned (REOs).

Freddie Mac reported the number of REO declined to 1,477 at the end of Q2 2021 compared to 2,812 at the end of Q2 2020. Fannie Mae reported the number of REO declined to 6,363 at the end of Q2 2021 compared to 12,675 at the end of Q2 2020.

This is a record low number of REO as the following graph shows:

From Fannie:

"The decline in single-family REO properties in the first half of 2021 compared with the first half of 2020 was due to the suspension of foreclosures that began in March 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the pandemic and with instruction from FHFA, we have prohibited our servicers from completing foreclosures on our single-family loans through July 31, 2021, except in the case of vacant or abandoned properties."

So we’d probably expect an increase in foreclosure activity to more normal levels once the foreclosure moratorium ended, even without COVID and the large number of borrows in forbearance plans.

However, even though the moratorium ended on July 31st, foreclosures will probably not increase much until 2022. From the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB):

Starting August 31, 2021, most mortgage servicers must tell you about your repayment or other options when they reach out to you. Except in limited circumstances, before January 1, 2022, a servicer cannot start the foreclosure process without first reaching out to you and evaluating your complete application for options to help you avoid foreclosure.

Even if lenders start the foreclosure process in January, it will take several months for the foreclosure to happen (states have different processes, but it will usually take 4 to 6 months from filing to foreclosure).

Probably around 1 million or so borrowers will reach the end of their forbearance plan in September and October. But most of these borrowers will probably make their payments or restructure their loans. And even for those borrowers who are unable to make their payments, this doesn’t mean we will see a huge increase in foreclosures.

As Mike Simonsen, CEO of Altos Research wrote on Twitter this week:

Mike Simonsen 🐉 @mikesimonsen

Mike Simonsen 🐉 @mikesimonsenAugust 24th 2021

1 LikeWith house prices up sharply year-over-year - up 16.6% nationally in May according to Case-Shiller - very few borrowers will have negative equity, and most seriously delinquent borrowers will be able to sell their house, as a last resort, and avoid foreclosure.

So, although foreclosures will increase from the record low levels, it will take some time (probably in 2022), and there will not be a huge wave of foreclosures like following the housing bubble.

https://calculatedrisk.substack.com/p/forbearance-delinquencies-and-foreclosure